Jacobi's Motor

Moritz Hermann Jacobi (German-speaking Prussian, naturalized Russian) is born in Potsdam in 1801. He moves to Königsberg (then Prussia, now Russia) in the beginning of 1833 and starts with experiments on horseshoe-shaped electromagnets.

In January 1834 he writes a letter to Poggendorf, editor of the Annalen der Physik und Chemie of his successes.

He now turns to the construction of a real electric motor, which he completes in May 1834.

This first electric motor set a world record in performance that stood for four years and was improved in September 1838 only by Jacobi himself. It was not before 1839/40 when other developers worldwide managed to build motors of similar and later also of higher performance.

A YouTube video of this motor is available.

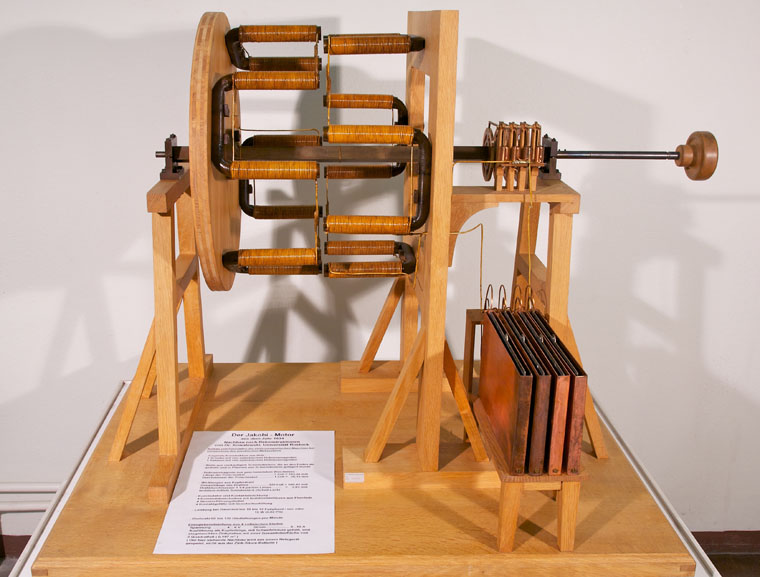

| The only picture of the motor is this steel engraving from 1835. The original motor no longer exists but a copy is in the Moscow Polytechnic Museum. Dr. Kowaleski from the University of Rostock has made a reconstruction of the motor. The German energy company Badenwerk had build two additional copies in 1992. One of them was donated to the Deutsches Museum in Munich, the other is now located at the Electrotechnical Institute (ETI) at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). The motor is fully functional and can be visited. Its power, however, doesn't come from the original sink batteries but from a hidden power supply. |

Supporting structure made of wood:

Horseshoe magnets forged of wrought iron:

|

The commutator |

Commutator and brushes:

Speed of rotation: 60 to 130 revolutions per minute |

Brushes and brush holder |

Energy supply from four voltaic pillars:

|

The zinc-acid battery |

|

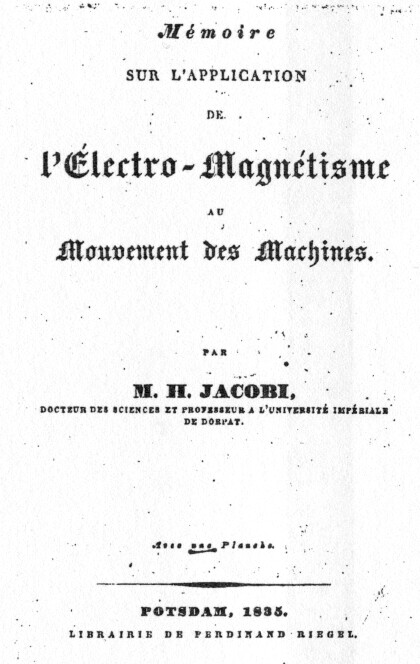

In November 1834 Jacobi sent a report on his engine to the Academy of Sciences in Paris and in Summer of 1835 he publishes a detailed scientific memorandum. This paper later earns him an honorary doctorate from the philosophical faculty of the University of Königsberg. By this lucky circumstances all of the engines data is known in exact detail today. His text is decided into 23 sections and was extended in 1837 with a further 15 sections. In his memorandum Jacobi expressly does not claim to be the inventor of electric motors. He acknowledged the work of others before him, namely Botto's and Dal Negro's. However, Jacobi is undoubtedly the first to demonstrate a useable rotating electric motor. |

|

At the request of the Tsar of Russia Jacobi moved to Saint Petersburg in August 1838 after he had lived in Doprat (now Tartu in Estonia), where he was appointed as professor of civil architecture in the German-speaking university in June 1835.

In St. Petersburg he is welcomed at the Academy of Sciences generously supported by Tsar in its further work on the electric motor. He begins his cooperation with Emil Lenz. Together they explore electromagnetic phenomena over the next decades.

On 13 September 1838 Jacobi demonstrates on the river Neva an 8 m long electrically driven paddle wheel boat. The zinc batteries of 320 pairs of plates weight 200 kg and are placed along the two side walls of the vessel. The motor has an output power of 1/5 to 1/4 hp (300 W). The boat travels with 2,5 km/h over a 7.5 km long route, and can carry a dozen passengers. He drives his boat for days on the Neva. A contemporary newspaper reports states the zinc consumption after two to three months operating time was 24 pounds.

On 8 August 1839 Jacobi tests an improved engine with three to four times mechanical power compared to 1838 (about 1 kW). His boat is now reaching 4 km/h. A key factor is the improved zinc-platinum battery (after William Robert Grove), which he has made himself.

In October 1841 Jacobi demonstrates once again a further improved machine, which is only slightly superior to the model from 1839.

Afterwards, he turns to developing a theory of the electromagnetic machine and publishes several scientific papers. His work culminates in 1850 in a lecture at the Academy in St. Petersburg.

Jacobi takes the Russian citizenship in 1848 and dies in St. Petersburg in 1874.

Literature

H. Lindner, Elektromagnetismus als Triebkraft im zweiten Drittel des 19. Jahrhunderts, Dissertation TU Berlin, 1986

P. Hempel, Deutschsprachige Physiker im alten St. Petersburg: Georg Parrot, Emil Lenz und Moritz Jacobi im Kontext von Wissenschaft und Politik, Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1999